Intro: Here in Northern Ireland, Ulster-Scots heritage is all too often trivialised, used as a commodity to soak money from public funders, politicised and poisoned - and often by those who claim to be its firmest advocates. Meanwhile from across the Atlantic comes an example of the depth and quality of work which could also be done here, if the 'decision makers' only understood the value of what we have under our very feet.

(article below reproduced from this website)

..........................

For more than 30 years, UNC Chapel Hill folklorist Daniel Patterson spent spring breaks and vacations roaming old cemeteries in the Piedmont region of the Carolinas.

Dodging poison ivy and black widow spiders, he photographed weathered gravestones when the light was just right, so he could read the carvings; often he sat for hours, watching until that moment arrived.

At first, it was a casual hobby, sparked by curiosity over markers similar to those he’d seen in New England and read about in Northern Ireland.

Then, while tramping through such historic church cemeteries as Thyatira Presbyterian in Rowan County, Steele Creek Presbyterian in Charlotte and Waxhaw Presbyterian in Lancaster County, S.C., Patterson began to notice a certain gravestone style rich in artistic design, poetic inscription and professional detail. The carver didn’t sign the stones, but Patterson sensed they came from a single source.

Through painstaking research, he traced the markers back to a shop near Charlotte run by members of the Bigham family in the 18th century. By the late 1970s, Patterson’s hobby had turned into a passion.

Decades of intensive field work and digging into archives and little-used manuscripts have produced a book that not only examines the unique Bigham headstones made before and after the American Revolution, but a vanished pioneer culture.

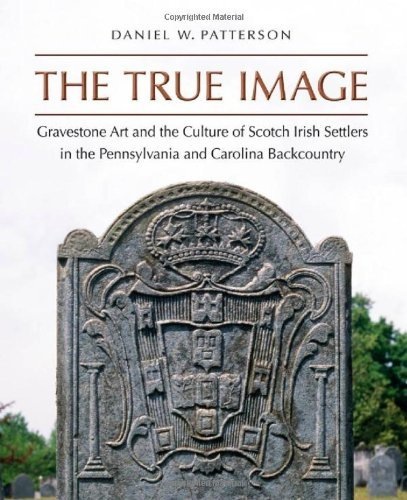

Published this month by UNC Press, “The True Image: Gravestone Art and the Culture of Scotch Irish Settlers in the Pennsylvania and Carolina Backcountry” is a story that also encompasses how people lived during the violent times of the Revolution, their political and religious battles along with providing new insights into slavery.

David Perry, editor-in-chief at UNC Press, doubted Patterson would ever finish the book he’d been working on for so long. When the author, who is 84, finally turned in a massive manuscript, Perry took a “big gulp.”

“It was daunting,” he said. “I was expecting a catalogue of old gravestones. Instead, Dan gave us a world.”

Looking through the lens of three generations of Bigham carvers and their circle of apprentices, Patterson has produced a work Perry thinks will appeal not only to specialists, but a wider readership interested in families and history.

“This book will be around a long time,” Perry said. “It will remind us of who we are, how we got here and what we hold dear.”

Tom Hanchett, historian at the Levine Museum of the New South, said Patterson is a highly respected educator who for many years headed the folklore curriculum at UNC Chapel Hill.

“He trained generations of scholars to appreciate the traditions passed down to us today,” Hanchett said. “This book is his life’s work.”

The names and dates on old gravestones are keys to “helping us understand how people fit into a larger culture,” Hanchett said. “It’s a great way to see local culture at work.”

Linda Blackwelder, who helped Patterson research the history of the Steele Creek community, urged him “to hurry up and finish the book.”

“I told him ‘I’m gonna die before you get it finished,’” she said. “I’m excited he has completed it. I’m glad he’s made a record of these stones. They’re eroding. They’re all melting away and it makes me sick.”

Bigham family member Earl Pike connected with Patterson years ago and read early chapters of the book. He’s been looking forward to the finished work.

“I’m thrilled to death Dan has done this,” said Pike, 78, of College Station, Texas. “I’m going to pass it on to my children. They need to know something about their ancestors.”

A Greensboro native, Patterson is the author or editor of nine books, including “The Shaker Spiritual,” “Sounds of the South,” and “A Tree Accurst: Bobby McMillon and Stories of Frankie Silver.”

“The True Image” is particularly fulfilling. The burying grounds of North and South Carolina became windows into the past, allowing him to unlock some of the region’s mysteries.

As Patterson explored old cemeteries, he found the stones were mostly made by unskilled hands helping their families or neighbors.

But the Bigham work was different. These markers came from skilled, creative craftsmen who turned out what Patterson calls “a surprisingly large and impressive body of work.”

Making the Bigham connection wasn’t easy. In his spare time, Patterson left his Chapel Hill home and drove to old cemeteries scattered from Hillsborough to Chester, S.C. He walked the grounds, collecting names of deceased persons and dates from the markers.

Then he took the list to the State Archives where he explored old records. Probates were especially helpful. Families listing their deceased relative’s possessions might include a receipt for a gravestone, naming the person who made it.

Traces of the Bighams weren’t left behind in letters or diaries. Patterson had to dig the story from deeds, marriage bonds, probates, court minutes and Revolutionary pension applications. Of special help was a privately printed family history supplied by the descendant of another stonecutter in Chester County, S.C.

“It was slow going,” Patterson said. “Tedious and time-consuming.”

Ultimately, he identified about 1,000 stones from the Bighams and their apprentices. The markers – the earliest surviving art of British settlers in the region – were scattered across 11 counties in North and South Carolina and in Pennsylvania.

Patterson looked at all aspects of the stones – designs, motifs, inscriptions. He began to see cemeteries as “art galleries and little libraries … used for storytelling.”

At Sugaw Creek Presbyterian Church cemetery in Charlotte, Patterson found a Bigham marker with the names of four children who died within four consecutive days of each other in 1781.

Patterson wrote: “The stone has no explanatory inscription, but only the coat of arms, as if having lost so much of the future in so short a space, the family stayed itself with a tight grip upon the past.”

A church history provided an answer to what had happened. The children’s’ 16-year-old brother came home from the Battle of Kings Mountain on Oct. 7, 1780, suffering not only from a gunshot wound but smallpox. The battered teen soldier survived. But smallpox brought down his younger sisters and brothers, one by one.

Early one morning, as sunlight raked across a flat gravestone at Hopewell Presbyterian Church Cemetery in Mecklenburg County, Patterson saw shadows fall into the cuts carvers had crafted on the surface. And that made something magical happen: Previously invisible words appeared on the stone.

It looked like poetry – put on the 1815 marker of prominent citizen Richard Barry, the son of one of Charlotte’s founders. The words were hard to read, but Patterson managed to get them down and research the inscription on the Internet.

He found the epitaph came from “Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, by Phillis Wheatley, Negro Servant to Mr. John Wheatley of Boston, in New England,” the earliest book by an African-American poet.

Born in Africa, Phillis Wheatley had been a slave since the age of 7. Her poetry book had been published in London in 1773 – 11 years before her death.

“The member of the Barry family who devised the epitaph knew the volume well, for the lines bind together couplets from three of Wheatley’s elegiac poems,” Patterson wrote.

Why a white Southern family in pre-Civil War Mecklenburg County picked lines from a black poet for their kinsman’s marker is an intriguing question.

To Patterson, it appears they were “making a statement … that they disapproved of slavery.”

He couldn’t answer all the questions that arose while writing “The True Image.” But he tried – mining as much information as possible.

The job that once seemed never-ending is done. And Patterson hopes it will appeal to anyone interested in the region, its early history and people.

“I had no idea I’d ever finish this,” said Patterson. “Now, it feels good to get it over with. It’s been wonderful fun. And also exhilarating.”

..............

• Order the 544 page book on Amazon for £42.50

- click here

Saturday, October 27, 2012

The True Image: Gravestone Art and the Culture of Scotch Irish Settlers in the Pennsylvania and Carolina Backcountry

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 comments:

Post a Comment