(It is very possible that Ernest Milligan’s children, and certainly grandchildren, are still alive today. If so, I would be delighted to hear from them, especially to correct any errors in the attempted biography below, and indeed in this series of posts. This one has been assembled from two interviews Ernest gave in ‘Irish Freedom’ and a fairly thorough trawl through the British Newspaper Archive.)

Ernest Henry Marcus Milligan (1879–1954) was born in Belfast. He was educated at Methodist College Belfast, after which he went to Queen’s University to study medicine, passing his first medical examination there in July 1899. It seems that he also studied Law for a time at Trinity College Dublin.

In early 1897 his influential sister Alice Milligan (14 years older than Ernest) recommended that when he was next in Dublin he should meet with James Connolly, who had been contributing to her magazine Shan Van Vocht. Ernest also contributed to Shan Van Vocht. Ernest’s reminisces of his time with Connolly were published in June and July 1943 in a two part article in the pages of Irish Freedom magazine (PDFs are online here). A mixture of youthful exuberance and ideology would drive Ernest’s energies for a number of years.

Ernest Milligan and James Connolly

When he and Connolly first met in early 1897, Ernest was 18 and Connolly was 26. In that interview Ernest described himself as –

‘a member of the Gaelic League and an ardent Nationalist, with my head full of ’98 and its horrors … I was more or less a Socialist, of the Christian Socialist type … I could not understand why all true Christians were not communists!’.

Ernest echoed Alice’s activism, which he surely would have observed and learned from. Even though just 19 years old, he founded the Belfast Socialist Society in September 1898, with members such as Robert Lynd and Arthur Gaffikin, a former Salvation Army man. This book also refers to Samuel Porter and James Winders Good, and Milligan made efforts to recruit William Walker (Wikipedia link here; one interesting text of later dispute between Walker and Connolly is online here.). There was also a 'Christian Social Brotherhood' in Belfast at the time and Milligan joined it as well. Gaffikin and Milligan took to the streets, attracting crowds in Sandy Row (but they were soon chased out) and the poorer parts of the city. Milligan’s mother Charlotte came along too and supplied refreshments to the crowds.

Ernest Milligan and James Connolly were in regular contact through 1897 and 1898; Milligan sold The Workers' Republic newspaper around Belfast, but he said that the Catholic Church banned the paper and sales fell. In 1898 he was a committee member of the Belfast Gaelic League and also a key member of the Irish Socialist Republican Party. His signature appears on an Irish Socialist Republican Party accounts book, from the years when he sold the newspaper on the streets.

But in 1899 Ernest Milligan fell ill, he recalled that this happened just a few hours after a meeting with Connolly. It resulted in Milligan being bed-ridden for six months, with an enforced break from his university studies for a further 18 months, not fully recovering until 1902–3.

Less Radical

Perhaps this illness dulled some of his ardour for the ‘cause’, or at the very least took him away from revolutionary politics, as he appears to have settled down into comfortable Belfast and north Down life. In 1902 The Northern Whig printed a letter from Milligan as a member of Bangor Rugby Football Club, complaining about a technicality in the rules of the game. That same year he was a founder member of Ballyholme Sailing Club, and in 1903 was pictured at a club meeting, sitting right beside James Craig, the future first Prime Minister of Northern Ireland.

Ernest Milligan resumed his studies and passed his second medical examination at QUB in April 1902, his third in May 1903, then Trinity College final professional examinations in January 1906, for which he was congratulated by his fellow members of Ballyholme Sailing Club. He finally gained his Royal University of Ireland M.B. B.Ch. B.A.O. in May 1906.

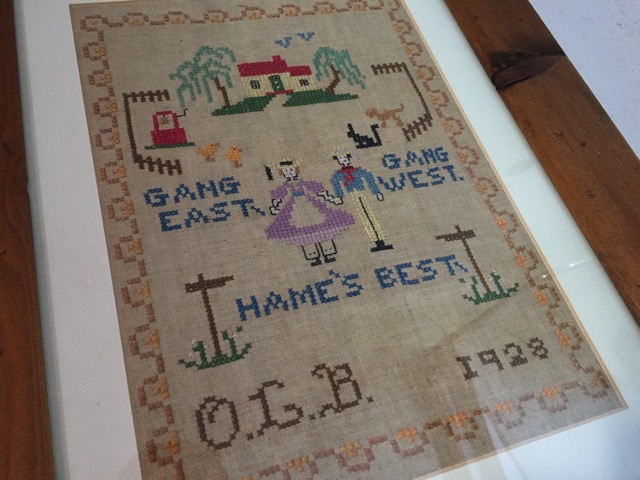

Ernest Milligan’s Ulster-Scots influenced Up Bye Ballads (December 1907)

I don’t yet know when he began to write the poems which would eventually form Up Bye Ballads, but some began to appear in the Northern Whig. 'The Braw Whin Bush' appeared in the Whig on 22 June 1907, openly attributed to Ernest Milligan, composed in praise of the humblest of all hedgerow flowers, with the final line urging ‘Men of Ulster, let your token be the braw whin bush!’ A few weeks later on 6 July, 'The Auld Red Cart' appeared in the same paper, again with Ernest Milligan named as the writer. There may have been more in the Whig, but it was December 1907 when a 54 page collection entitled Up Bye Ballads was published, printed by W&G Baird, under the pseudonym 'Will Carew', with a cover price just one shilling. I’ll work through them in the next, final, post in this series.

What the significance of ‘Will Carew’ was as a choice of name, I’ve yet to discover, and it's all the more odd given that Ernest Milligan had already been named in the Whig as the author of some of the individual poems. There had been a character of that name in a boys' adventure story from 1884 entitled Charlie Asgarde: The Story of a Friendship.

Media Reviews

Press reviews were positive. The Tyrone Constitution reproduced a few verses of ‘The Braw Whin Bush’ and said it was a

’neat little volume … the majority of the poems are written in the County Down dialect, and it will be found that the author has been true to the characteristics of that county … delightfully characteristic ballads.

The Londonderry Sentinel said it was –

’… a collection of quaint Ulster verses, of tuneful rhythm and much readableness. The writer has a good style and tells his little rural stories well’.

The Irish News also reproduced some of ‘The Braw Whin Bush’ and said the collection was –

‘… sparkling … an Ulster work if ever one was published. The writer we believe knows and loves Co. Down best; though we venture the opinion that the “dialect” which he uses in many of these poems is more redolent of Ayrshire than of Banbridge … Carew’s “dialect” may be that of the Mourne Mountains or the Antrim Glens, or the “banks and braes of bonnie Doon” … Mr Carew’s printed speech of the North-East differs little from that of South-West Scotland; and Ayrshire recalls Robert Burns. The clever author of 'Up Bye Ballads' has read the immortal Ploughman, but he has not once consciously imitated him … charming little treasury of Ulster song ...'

By far the most interesting review I have found, yet again quoting ‘The Braw Whin Bush’, appeared in the Dublin newspaper Freeman’s Journal and National Press on Burns Day 1908, which in many ways reinforces the ’three cultural strands’ concept, with Ulster-Scottishness a distinct element –

In these days, when the chief city of Ulster and many towns and country districts all over it are become working centres of the Gaelic revival, a book of verse like this will almost a shock to the Irish-Ireland reader. He has been busily working for the de-Anglicisation of the Irish nation, looking forward to an era when the West British shoneen will be extinct, end behold here is reminder that there exists within the borders of our island country population which is not West British nor shoneen, which has not got to be de-Anglicised, for the simple reason that its speech is not English, as we know it, but Lowland Scotch.

The people speaking tongue are to found mainly Antrim, Co. Down, but also on extensive tracts of land in the North-West, coming right against the Gaelic frontier of Tir-Conal, in the Laggan district, it is called, in Donegal. But let not the Irish-Irelander brand those survivors the Ulster Plantation as aliens and foreigners. This Scotch-Irish dialect, so ragged and almost distasteful to our hearing, was the speech of men who stood side by side with the Northern Catholic Gaels on the battlefields Antrim, who camped on the wooded height of Ednavady, and lined the ditch behind “Saintfield Hedge in the County Down.” was the mother tongue James Hope, and the congregations of those United Irish Presbyterian worthies, Porter, and Steele, Dickson, Kelburn, and Warwick.

It a pity that there is nothing in the little volume before us to recall the patriotism the men of Down, not a single verse echoing the spirit of fine old street-ballad that might well have served as a model:

All the same we welcome this volume as evidence of the fact that the Scotch-Irishman has not lost the gift of song. The subjects are homely and natural; the verses fluent and tuneful. The satire in “The Ministers Call” and “The Six Road Ends” will be appreciated in Presbyterian circles. There are local poems for many of the North Down villages – Carrowdore, Comber, Donaghadee, Ballylesson and Bangor.

Marriage in 1908 – departure for England 1911

In December 1908 he married Sara M’Mullan of Grange, Armagh, at Grange Parish Church. As a newly qualified doctor he was involved in the establishment of the new Belfast branch of the Womens' Health Association at a high society event in City Hall in October 1907. On 12 October 1909 the Irish News printed a poem he had written in praise of Queen’s University, entitled 'Welcome! Q.U.B.'. In 1910 he was a member of Royal Belfast Golf Club, among the cream of Belfast merchant wealth and gentry. In July 1911 he gained a Diploma in Public Health from Dublin University.

Medical career in England, 1911

Summer and studies over, he and his wife Sara moved to England. In September 1911 he was appointed as Certifying Surgeon for the Long Eaton district of Derbyshire. He was a medical officer in Bath from August 1917-1920 (there are suggestions that Alice and their brother William stayed in Bath around these years). In August 1920 he took what might have initially have been a part-time role in Glossop on the east side of Manchester, but eventually he moved back north permanently, becoming a well-loved figure in the Glossop community and medical professional circles in England for the rest of his life. You can read his biography here on www.GlossopHeritage.co.uk, including an article about his invention of a toffee sweet, fortified with whey and peanuts, to give wartime children extra nutrition. Products like this are still used in Africa by aid agencies today. Here is a 1943 newspaper photograph:

The Book of Irish Poetry, 1915

During all of this, his poem ‘Six Road Ends’ from Up Bye Ballads was selected for inclusion in The Book of Irish Poetry, a collection (online here) dedicated to Douglas Hyde, son of a Church of Ireland rector who became the first President of the Gaelic League, and first President of Ireland. Perhaps he and Ernest were friends.

July 1927: Letter for ‘improving partition relations between the North and South of Ireland’

This letter, to William X O’Brien, would be worth a read, written from Ernest’s home of Spire Hollin House in Glossop.

1930s playwright and BBC Radio broadcasts

Even though now he was focussed on a busy medical career in Glossop, in the 1930s Ernest Milligan found the time to write a number of plays, some for BBC Radio - tantalisingly The Ballad Singer (June 1933; of which a Belfast News Letter review said that ’the majority of the songs in this play were collected and arranged by the author himself). Here’s an advert which lists some of the performers:

He also wrote Muggleston on the Map: A Municipal Mockery (1934), The Mayor Chooses A Wife (1935) and ’Twas In Old Ireland Somewhere (1936; said to be set in ‘an Ulster farmhouse not far from a thriving town on the evening of the monthly fair). Below is an extract of a Whig article from 24 April 1936.

1938: ‘An Ulsterman’s Plea’

On 27 October 1938 a letter of this title from Milligan appeared in the Northern Whig, a powerful appeal to God’s providence, to prayer, and to the growing threat of Germany and Nazism, stating ‘these are grave times. The very fundamentals of religion as well as our liberties are in danger… Ulster can initiate a new and better epoch in a troubled world…’.

The deaths of Alice and Ernest Milligan

When Alice died on 13 April 1953, Ernest made contact with a well-known Irish Republican Brother W.P. Allen to ask him to write a biography of her. Allen collected all of her papers and stored them, but never wrote the biography. Apparently these archives are now in Omagh Library (see page 97 here).

Ernest died less than a year later, at Hadfield in Derbyshire on 21 March 1954, aged 75, and was buried at Glossop cemetery. You can read his obituary here on GlossopHeritage.co.uk. An obituary also appeared in the Belfast News Letter.

Final post to follow...