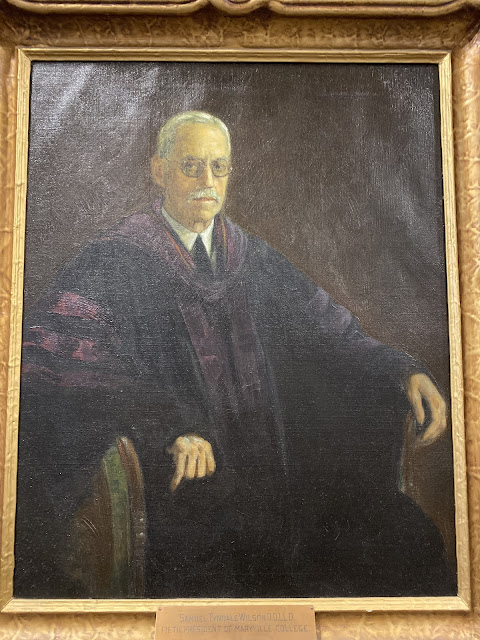

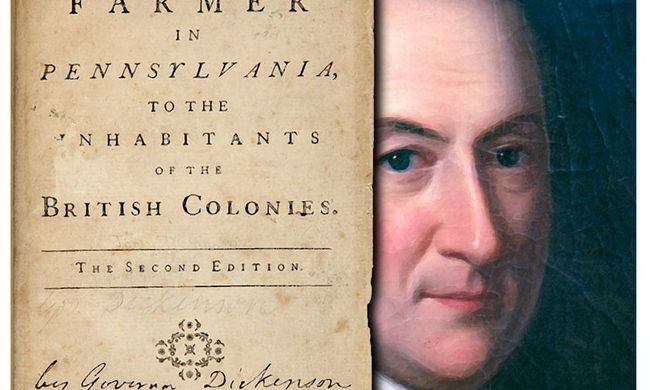

Rev. Daniel Eagle Nevin was the minister of Sewickley Presbyterian Church, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (shown above). His family ancestry included McCrackens on his mother's side, and Williamsons on his father's side. Nevin was a great-nephew of Hugh Williamson, the son of Ulster emigrants who was a witness to the Boston Tea Party and who was quizzed about it in London, and who wrote his famous The Plea of the Colonies* - Wikipedia here.

Here is how Nevin understood and expressed the Scotch-Irish community story, undoubtedly passed down to him by his family -

“religious liberty ... democratic ideas ...

... It was the amplification of these twin doctrines, aided by an old grudge against a government, which, – notwithstanding their prowess at Londonderry and the Boyne – had never done them justice, that furnished them with sufficient reasons for assuming in their adopted country the initiative in the American Revolution – by resisting on the banks of the Alamance the militia of Gov. Tryon in 1771, and promulgating from Mecklenburg Courthouse, North Carolina, in May 1775, the first bold manifesto looking firmly at the scheme of colonial independence.

The same doctrines endeared yet more and, consecrated through conflict and trial, drew from the mountains and valleys of Pennsylvania, Virginia and North Carolina, to meet the demands of the Revolutionary contest, a hardy intelligent yeomanry whose inflexible devotion to popular liberty has justly won for the Presbyterian Bluestocking the highest grade of canonisation in the temple of freedom....

...It was their glory to be the great champions in America of the rights of the soul. Paul before Agrippa, or Luther at Worms, furnished not to Italian or Flemish artists a purer or more elevated study in moral aesthetics than is presented in Makemie's trial at New York, 1707, for preaching without Lord Cornbury's license the gospel of the Lord Jesus Christ ..."

– Rev Daniel Eagle Nevin (1813-1886) of Sewickly Presbyterian Church, Pennsylvania, writing in The Mercersburg Review, 1851 (online here)

• Look at his four key reference points - the Bible (Paul and Agrippa), the Reformation (Luther at Worms), the Glorious Revolution (Londonderry and the Boyne), and individual liberty (Francis Makemie). These fuelled the Scotch-Irish community's justification for revolution in America, shown at Alamance and expressed at Mecklenburg.

LINEAGE

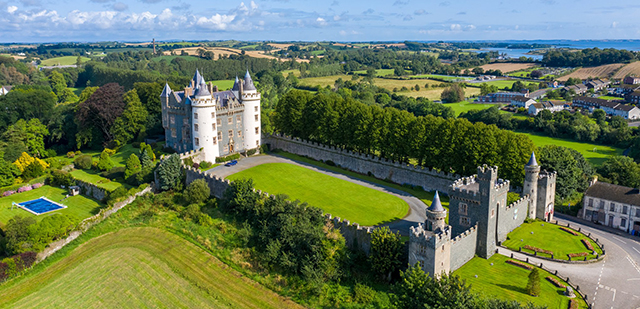

The lineage here is interesting too. Hugh Williamson was born in 1735 and died in 1819. His great-nephew Daniel Eagle Nevin was born in 1813 and died in 1886. Their lives span 150 years and overlapped by six years. Potentially, Hugh's parents or grandparents would have endured the Siege of Derry, which is the port that his mother had emigrated from. In The Plea of the Colonies, Hugh made the blockade of Boston of 1774 sound a lot like the Siege of Derry of 1689:

“the whole town of Boston, unheard and untried, was immediately condemned to suffer that kind of extreme, inadequate punishment which savours of revenge … a fleet and army sent to intimidate and distress the inhabitants … like beasts and not like men … you then cut off their fishery and lest starvation should make them more refractory, you sent more troops”.

Daniel had a brother who was another Presbyterian minister in Pennsylvania, called Rev Alfred Nevin (1816-1890). Alfred wrote numerous books, including this one - Churches of the Valley: Or, an Historical Sketch of the Old Presbyterian Congregations of Cumberland and Franklin Counties, in Pennsylvania, which is online here.

"WHAT COULD TEMPT SUCH PEOPLE TO BECOME INDEPENDENT?"

*Again, in The Plea of the Colonies (1775) Hugh Williamson shows that, rather than being anti-British, right up to the 11th hour the colonists' campaign was that, in terms of rights and liberties, they should be fully British:

“whoever was best acquainted with the colonists had the least reason to believe that they were looking toward a state of independence. As members of the British empire, they have enjoyed, till the beginning of the present controversy … as much liberty as was consistent with civil government, or as much as they could possibly expect … they were conscious of the blessing, they prayed for its continuance. They esteemed Great Britain as a parent, they loved her with more than filial affection; they loved every thing that was British; they were to a man zealously attached to his Majesty, if we except a few individuals who migrated to that country in the year forty-five. What could tempt such people to become independent?”

• the 1926 Historical Sketch of Sewickley Presbyterian Church is online here.