I think it’s quite right that in recent years there has been an interest in finding and telling the women’s stories from history - without those we have only half of the picture. However, often they are hard to find as history has often been written, not just by men or for men, but focussed on the major political or military events. Plenty of men are also invisible within that historical record because they were ordinary, unimpressive, lower-class and - for publishers and writers at least, with books to sell - uninteresting. These men enjoy no ‘privilege’ either - forgotten and left out, or mere cannon-fodder statistics.

The American Revolution is something of an exception in that you do find women’s stories more frequently there. The 1848 three volume set Women of the American Revolution (online here) is a good example of that.

Catherine Clyde (1737-1824) (original surname Wasson) is a woman I have just recently found while researching Matthew Thornton, the Ulster-born signer of the Declaration of Independence. Here is a long extract about her, from this 1903 biography of Thornton.

Matthew Thornton had a niece, named Catherine Wasson, who bore a brave and useful part in the Revolution. She was the daughter of a sister of Matthew Thornton, named Agnes, who married Dr. James D. Wasson, and she was born in Leicester, Massachusetts, in 1737. Dr. Wasson and his wife were among the early settlers of the New York frontier, where their home was at Amsterdam, near the Mohawk River. There Catherine Wasson knew as a playmate of her brothers, Joseph Brandt, or Thayendanegea, who, as chief the Mohawks, subsequently wrought such havoc throughout the New York frontier.

Catherine Wasson was married in 1761, at Schenectady, to Colonel Samuel Clyde, whose father, Daniel, had emigrated from Londonderry, Ireland, to Londonderry, New Hampshire, about 1732. The Clydes came originally from the River Clyde in Scotland. In 1762 Colonel Clyde and his wife moved to Cherry Valley, where six years, later he purchased a farm about a mile from the present village, the ownership of which has to this day remained in the Clyde family ...

Mrs. Clyde took charge of the farm, with her young children. She did all she could to redeem it from the wilderness and to encourage them in their labors. Colonel Clyde, by his kindness of heart and sympathy for unfortunate debtors, became financially embarrassed, and after his death in 1790, his farm was sold at sheriff's sale. Mrs. Clyde bought the farm, and by the help of her children paid for it. She died on May 31, 1824, at the age of 87, and was buried in Cherry Valley on the ground occupied as a fort at the time of the massacre.

Morrison, in his history of Windham, New Hampshire, says of Mrs. Clyde that she was patriotic, resolute, energetic, had a fine education, and was a woman of fine character. Hon. J. D. Hammond, who was personally acquainted with her, said of her :

"During the revolutionary war she embraced every opportunity to converse with young men, and to impress on their minds the inestimable value of the rights for which America was contending, of the duty of all citizens to hazard everything, even life itself, in their defense, and of the glory which would be the reward of patriotism. These conversations are said to have had a great effect on the minds of those to whom they were addressed."

Many of the children of Mrs. Clyde, whose lives were so bravely saved by her, and their descendants, afterwards attained distinction, both in civil life and in the service of their country in the Civil War.

The Clydes were caught up in the Cherry Valley massacre of 1778, in Otsego County, New York State, when the heavily Scotch-Irish fort and settlement was attacked by a combined force of British and Native Americans. Catherine and her children hid in a nearby forest. A detailed description is online here.

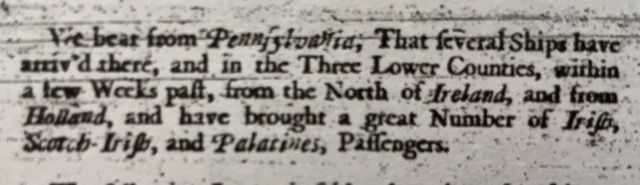

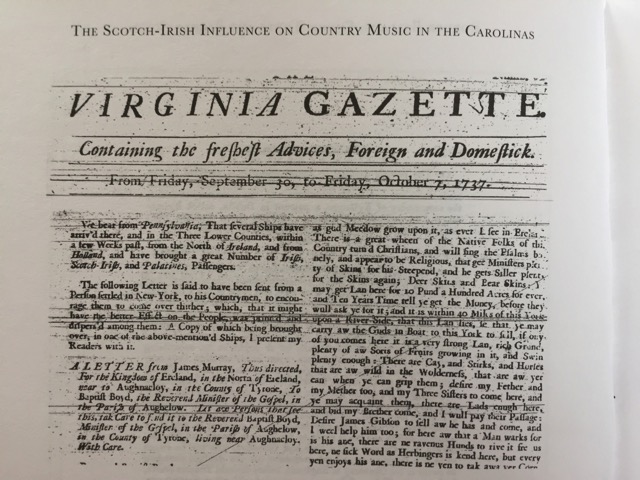

The 1831 book Annals of Tryon County; the Border Warfare of New York During the Revolution by William W. Campbell (online here) has further accounts, including yet another early usage of ‘Scotch-Irish’:

In New-York, Mr. Lindesay became acquainted with the Rev. Samuel Dunlop … he was an Irishman by birth, but had been educated in Edinburgh; had spent several years in the provinces, having travelled 'over most of those at the south; and at the time of his first acquaintance with Mr. Lindesay, was on a tour through those at the north. He went to Londonderry in New-Hampshire, where several of his countrymen were settled, whom he persuaded to remove, and in 1741 David Ramsay, William Gallt, James Campbell, William Dickson, and one or two others, with their families, in all about thirty persons, came and purchased farms, and immediately commenced making improvements upon them.

They had emigrated from the north of Ireland several years anterior to their removal here; some of them were originally from Scotland; they were called Scotch Irish—a general name given to the inhabitants of the north of Ireland, many of whom are of Scotch descent; hardy and industrious, inured to toil from their infancy, they were well calculated to sustain the labours necessary in clearing the forest, and fitting it for the abode of civilized man.

• Further biographical information on the Thorntons is available online in this 1905 book The Family of James Thornton.