Background and Intro

We should have been in Fife, one of my favourite parts of Scotland, for a week over Easter but the current coronavirus 'lockdown' ended that. I've been visiting Fife off and on since 1991 when I was 19 and had completed my Foundation Year at the University of Ulster's Art College in Belfast and had interviews lined up to do a three year design degree at various art colleges including at Glasgow, Edinburgh and Dundee. So I travelled around Scotland by bus and train for about a week in April '91 and crashed on spare beds and sofas of various friends' student accommodation in Glasgow, St Andrews and Dundee. Below is a photo of one my mouldy bus tickets from my scrapbook of the trip.

Fife is superb grain growing country, as demonstrated in the small village name Kingsbarns and the distillery there – when I visited it last year a staff member I dealt with had family in Bangor. Fife's 'East Neuk' is a necklace of beautiful wee fishing villages, much prettier and better conserved than those of my own Ards Peninsula.

Fife has a strong sense of its own identity, with the Firth of Tay to the north and the Firth of Forth to the south, with road and rail bridges across both. It proudly calls itself 'the Kingdom of Fife', thanks to a Pictish kingdom of the 6th century. King Robert the Bruce is of course buried, sans heart but with bronze-cast skull, in Dunfermline Abbey. The Scottish Reformation first took off in 1520s St Andrews and then Dundee. 100 years after that the Covenanters were strong in the area – Richard Cameron was born in Falkland around 1647-8 where a plaque marks his home. Renowned Ulster Presbyterian minister of Bangor, Robert Blair, completed his career at Aberdour where a large memorial plaque on the exterior of his last church commemorates him. Robert Echlin, the episcopal Bishop and fervent opponent of Blair and all of those first Ulster-Scots Presbyterians (who, on his death bed, famously said he was dying of a 'guilty conscience') was from Fife before he relocated to Ardquin near Portaferry. Fife also has a rich Scots language tradition, as Mary Murray's famous 1982 In My Ain Words book shows. The song my mother taught me called Some Say the Divil's Deid (and buried in Killarney) has a Fife version Some Say the Deil's Deid (and buried in Kirkcaldy). Even Johnny Cash's ancestry has been traced back to the village of Easter Cash in Fife.

As this previous post shows, on a July 2008 visit to Fife I got up very early to go to the town of Cupar, just to take a photograph with the sun at the right angle of the gravestone of the Covenanter David Hackston (Wikipedia entry here) at Cupar Parish Kirk, who had been executed in Edinburgh on 30 July 1680. The previous year of 1679 had seen major state repression of the Covenanters and the consequent battles at Drumclog and Bothwell Brig where Hackston had been in a command role. He was one of a group who had planned to ambush the Sheriff of Cupar, but they ended up killing the Archbishop of St Andrews, James Sharp, instead. We were back in Fife again last February and I stopped off at Cupar to see Hackston's gravestone again. The only part of his quartered, dismembered, body that was buried there was his hand, which is why it is the central carving on the ornate stone, with a memorial poem on the reverse side.

As this previous post shows, on a July 2008 visit to Fife I got up very early to go to the town of Cupar, just to take a photograph with the sun at the right angle of the gravestone of the Covenanter David Hackston (Wikipedia entry here) at Cupar Parish Kirk, who had been executed in Edinburgh on 30 July 1680. The previous year of 1679 had seen major state repression of the Covenanters and the consequent battles at Drumclog and Bothwell Brig where Hackston had been in a command role. He was one of a group who had planned to ambush the Sheriff of Cupar, but they ended up killing the Archbishop of St Andrews, James Sharp, instead. We were back in Fife again last February and I stopped off at Cupar to see Hackston's gravestone again. The only part of his quartered, dismembered, body that was buried there was his hand, which is why it is the central carving on the ornate stone, with a memorial poem on the reverse side...............................................................................................................

Ulster's connections with Scotland are usually assumed as being with the west coast, but in fact they reach into almost all parts of the country. The story below is just one of the many east coast links –

• of a driven working class Scot who moved to Ulster

• became a champion for temperance and land reform

• devoted much of his life to the right of tenant farmers to buy their parcels of land from the landlords

• became the MP for South Tyrone

• had a group of like-minds who became known as 'Russellites'

• for nearly 20 years was utterly committed to maintaining the United Kingdom and travelled its length and breadth to campaign for it

• but after all that, around 1900, changed his mind in what was later called 'an extraordinary volte face'

NB: I'm not into political history much, which I find is an area of either great expertise, or supreme geekery! It's the cultural and integrated Scottish/Ulster/Ireland/UK dimension of this man's life that interests me. And it's very easy to get lost in the weeds of the complexity of the 60+ years that land reform took, so this is just a simple attempt to assemble a story.

• Thomas Wallace Russell – birth and early life

• Thomas Wallace Russell – birth and early lifeThe part of Cupar in Fife known as the West Port was the birthplace on 28 February 1841 of Thomas Wallace Russell. He was the son of David Russell, a stonemason originally from nearby Kingskettle, and Isabella Wallace. David Russell had been a colleague of Hugh Miller, the stonemason's apprentice who became a famous geologist.

Thomas's grandfather had been evicted from his tenant farmstead and this burning family memory was Thomas's fuel throughout his life. The tenant right newspaper the Ballymoney Free Press of 13 March 1902 quoted him as saying –

"... I am the grandson of an evicted tenant – a man who left his all upon a Scotch farm and went out upon the world penniless and ruined. My father was silent. The grandson has broken out ..."

The family were Free Church of Scotland people; Thomas was educated at the Madras Academy in the town, after which he worked for a time in a grocer's shop.

• From Fife to Dungannon

Russell moved to Ulster in 1859 aged 18 and settled near Dungannon, possibly at Donaghmore. He always used his full name, or else T.W. Russell, perhaps to distinguish himself from his famous Ulster namesake and predecessor. He became secretary of the town's branch of the YMCA which was set up in September 1861 with Major Stuart Knox MP as its President and a young Thomas A. Dickson as its treasurer. It appears that, far from the corny Village People cliché of our era, the YMCA was a very well-connected organisation with the kind of networking opportunity that its ambitious members could make use of. The newspapers of the time have lengthy articles reporting on the activities and meetings of the Dungannon branch, many of which are authored by Russell.

In September 1863 Russell represented the Dungannon branch at the YMCA 'Universal Conference of Delegates' for one week in London. However, the co-operation between secretary Russell and treasurer Dickson would, 30+ years later, be turned to rivalry and rancour.

Russell became a paid representative for the Irish Temperance League and was highly active as a speaker on social reform all over Ireland, even lecturing in Scotland in the Union Street Hall in Cupar on his visits home. Russell honed his oratorical and writing skills quickly.

• Marriage and the move to Dublin

On 29 September 1865 aged 24 the Presbyterian Russell married Harriet Wentworth Agnew, the daughter of Methodist merchant Thomas Agnew of Dungannon, at St Anne's Church of Ireland in the town, with the service conducted by Rev William Quinn of Drumglass and Rev J B Kane of Annaghmore. Thomas and Harriet eventually settled in Dublin where around 1870 Thomas became an insurance agent, secretary of the Dublin Total Abstinence Association, and opened "The Russell Temperance Hotel" at 102 Stephen's Green South. He travelled all over Ireland championing the cause of temperance, and was a frequent lobbyist at the House of Commons where he became a familiar face.

• Land Reform

Ordinary people did not own land. In 1870, 97% of farmers – of all religious backgrounds in every county in Ireland – were tenants of landlords. A new law called the Landlord and Tenant Act was passed that year, By 1881 the Land Law Act was passed. Change was coming and land ownership was a massive political issue.

• Entry to Politics - Dublin and Preston

Aged 43, Russell stood for election in Dublin's Royal Municipal ward in 1884 as a pro-Sunday closing of public houses candidate, and one of his nominees was the Quaker tea and coffee entrepreneur Samuel Bewley Jr, a brand name still very famous in Dublin and Ireland today.

In 1885 Russell unsuccessfully stood as a Liberal Party candidate at Preston in the north west of England. It looked like he might win, but the vote was swung by a last-minute intervention from 'Parnellites' in Ireland to mobilise the Irish and Catholic population of Preston to vote Conservative to oppose Russell (source Fife Herald 23.11.1889).

Soon after, the leader of the Liberal Party, William Gladstone, introduced the First Home Rule Bill. So Russell left the party due to his Unionist convictions, but Land Reform was his real passion, and local campaigns to overturn landlord domination and allow tenants to buy the land were growing. But Gladstone's endorsement of 'Home Rule' brought a new, complicating, political context.

As ever, this caused polarisation in Ulster and Ireland with the all too familiar outcome. The fallout included the formation of both the Irish Protestant Home Rule Association and the Ulster Liberal Unionist Association.

• 1886: MP for South Tyrone

Back north to the Dungannon area and in 1886 Russell was selected as Liberal Unionist candidate for South Tyrone - an election he won, with a majority of just 99 votes, ahead of William O'Brien, who among many things was the editor of United Ireland (Wikipedia here) and the author of the "No Rent Manifesto" during a period of imprisonment in 1882.

That same year Russell delivered this searing address in Grangemouth, using a Biblical turn of phrase which I remember Alex Salmond also using some years ago –

"... What, I ask, have they (the Ulster Unionists) done that they are to be deprived of their Imperial inheritance, that in the words of the Apostle they are to be made ‘bastards and not sons’. Three hundred years ago Ulster was peopled by Scotch settlers … The men there are bone of your bone, flesh of your flesh … they read the same Bible, they sing the same psalms, they have the same church polity. Nor have they proved altogether unworthy of their ancestry…The descendants of these men have made Ulster what it is ..."

– quoted in Intimate Strangers: Political and Cultural interaction between Scotland and Ulster in Modern Times by Graham Walker (1995), p. 31.

However even in victory Russell divided local opinion - the Tyrone Constitution of August 1887 shows that a Church of Ireland rector called Rev Thomas Ellis, and a small but influential section of local Orangemen, were opposed to Russell's stance on land reform for tenants. Those who were supportive of Russell were quick to write letters of support to the paper, and so in September Russell organised a large public meeting of over 1000 people in Dungannon Market Square to state his case openly once again. Russell was never an Orangeman himself, but that particular meeting was chaired by Captain William Brown, the District Master of Castlecaulfield.

In 1889 when Russell was back in Cupar, he addressed the East of Fife Unionist Association in the fishing village of Anstruther (pronounced 'Ainster'), with the Fife News saying that "the visit will not fail to be the political event of the year on the coast". He also spoke in the Town Hall of Leven, a town said to be "the most impregnable fortress of Gladstonism". The land issue remained his overarching passion. Russell proclaimed –

"... the toiling artisans of Belfast and for the farmers and labourers of Ulster, who absolutely refused to take in exchange for the Imperial Parliament of Great Britain and Ireland a vestry on College Green filled by men who signed the 'No Rent Manifesto' ... a picture of Ireland that was repeatedly presented just now to the British elector showed that island as a bleeding country, crushed by unjust laws and coercion and trampled upon by a tyrannical and despotic Ministry.

But he spoke of a better island than that ... for Ireland the question of land was the supreme question... with an earnest appeal to Scotsmen not to cast their kinsmen of Ulster adrift ..." (source Fife Herald 23.11.1889)

He was on such a high after the meeting that he declared his intention to return to Scotland in order to stand in East Fife in the 1892 General Election, against the future Prime Minister, Herbert Henry Asquith. In 1889 the Sheffield Daily Telegraph said that –

"One of the most hated Unionist MPs is Mr Thomas Wallace Russell MP. He has earned the hatred of the Parnellites, both Irish and British, by the fearlessness with which he has upheld the cause of the Union; the unerring accuracy of his statements; and the unflagging diligence which which he has employed himself in personally acquiring information on the Irish land question".

The Dundee Advertiser of 3 February 1890 said that:

"Mr Russell is not an Irishman, nor an Ulster Scot, having first seen the light in Cupar Fife, but he is an Ulster member. He had the honour of defeating Mr W. O'Brien in one of the divisions of Tyrone ... he believes all he says and does not speak for mere effect ... although he has spoken the same speech scores of times, it is always like a hot lava stream. With the exception of Colonel Saunderson, Mr Russell is the only Ulster Unionist the constituencies on this side of the water are familiar with ... Mr Russell is not an Ulsterman at all and he is getting tired of going about alone telling Scotch and English audiences that the Ulster people are honest, industrious and prosperous. What is Ulster doing? How many of her members go out to meet the avalanche of lies with which Great Britain is deluged?".

• 1892: Russell v Dickson

In a year now best-known for the Ulster Unionist Convention in Botanic Gardens of 17th June, at which Russell was present (and was first to endorse a motion from the Lord Mayor of Belfast), he was reported as saying

"... the men of Ulster that day were, indeed, making history. They had no quarrel with their fellow countrymen, but they objected to the system of domination which their fellow countrymen would put them under ..."

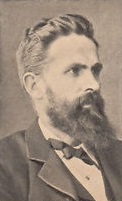

The contemporary illustration below shows Russell fourth, in between Rev Dr Richard Rutledge Kane and Thomas Sinclair.

Russell remained focussed upon South Tyrone and stood again as a pro-Union and Presbyterian candidate there in the July 1892 election. The twist in the story is that his opponent this time was his former YMCA pal Thomas A. Dickson, who was now a pro-Home Rule Presbyterian, and had previously been an MP for Dungannon from 1874-80, MP for Tyrone from 1881-85, and had also been MP for Dublin St Stephen's Green - where Russell's own Temperance Hotel was - from 1888-92 (Wikipedia here).

Russell won by 372 votes. The Freeman's Journal of 15 July 1892 detailed the rancour after the count, alleging Russell had 400 bogus votes. Dickson said he –

"... was defeated by the Presbyterian and Protestant farmers to whom he had devoted 18 years of his life... their eyes would be opened as to where their true interests lie ... he would never forget the support he had received from the Church of Ireland, from his own Presbyterian co-religionists he received nothing but the most unscrupulous opposition ... Presbyterian ministers standing beside ballot boxes and intimidating men who had voluntarily offered to vote for him..."

A momentum was now gathering around Russell as a figurehead within the broadly Unionist and Presbyterian rural community. At a meeting in Ballymoney Town Hall, organised by the renowned Rev J B Armour and at which Russell's old friend and recent adversary Dickson was due to speak, another speaker alleged that the Conservative party was being "led round on a chain like a performing bear ... dancing to the tune of Mr T.W. Russell" (Northern Whig 7 Sept 1894).

• Celebrity beckons

It is often unkindly said that politics is showbusiness for ugly people. Even though something of a lone figure, Russell was box office. A search for 'T.W. Russell' on the British Newspaper Archive for 1890–99 gives over 25,000 returns. He spoke at events the length and breadth of Great Britain and Ireland to large audiences. In June 1893 the periodical World ran a lengthy 'puff piece' entitled 'Mr T.W. Russell, M.P., Celebrity At Home' which reads like a lifestyle article in the Tatler or a segment from MTV Cribs, from his London townhouse home at Ashley Gardens, Westminster. It was widely reprinted in local weeklies like the Sheffield Evening Telegraph.

"... the decorations, the hangings, the furniture, and every aspect of the rooms bespeak what the argot of the day calls 'modernity' ... everything is as bright and cheerful and home-like as the loving labour of two charming women can make it. During the last season or two Mrs and Miss Russell have become known in London society...

during the past six or seven years few personalities have become better known to the public than Thomas Wallace Russell for he has traversed the entire kingdom and addressed over 800 public meetings in defence of the great cause to which he has devoted his life ..."

• 1894: Death of Harriet Russell

Suddenly, at what was then the high point of her husband's career, Harriet Russell died of pneumonia on 31 December 1894, at their home at 103 Stephen's Green, Dublin, aged 53. This followed 'a chill' she experienced on Christmas morning at a church service in a Methodist chapel close to where they lived. The funeral cortege left the house at 9.30am on 5 January bound for Amiens Street train terminus (now Connolly Station), to take her body back north to be buried in the Agnew family plot in Dungannon. The Dublin Daily Express of 1 January 1895 warmly remembered her charitable and temperance work, and reported that

"... his friends all over the United Kingdom will learn with deep sorrow of the affliction which has fallen upon him ..."

On 15 January the Northern Whig published the funeral tribute which had been given by Rev Dr M'Cheyne Edgar of Adelaide Road Presbyterian Church in Dublin, saying she had been Thomas's –

"... chief support, his best advisor, his most reliable co-worker ... a mind and will reinforced and strengthened by Christian principle ..."

The united choirs of the Presbyterian and Church of Ireland churches in Dungannon sang "For ever with the Lord, amen so let it be" just before her interment - a combination which says much about the Russells. Their daughter Edith was their only surviving child, an elder child having died in 1874.

Who knows what effect such a bereavement had on 53 year old Thomas Wallace Russell. But there are signs that his mind was starting to change.

• 1895: A Change is Gonna Come

The letters pages of the newspapers for January show that Russell was as active as ever, but the Northern Whig on 17 January quoted him saying, regarding the loss of his wife "... my first impulse would be to give up everything and retire absolutely from public affairs ... when the shadow passes a little I hope again to face those duties...".

Yet his more hardline Unionist opponents still harangued him in the press, often due to his frequent alignment with John Morley who had been Chief Secretary for Ireland. In February Russell penned this letter to Fortnightly Review, which was widely reprinted elsewhere –

"... I am a convinced Unionist. I have told the Ulster farmers that I am a Unionist first and a land reformer after that. But why am I devoted to the Union? It is because I believe that the Imperial Parliament is alike able and willing to do everything for Ireland better than an Irish Parliament can possibly do it.

Take this belief away, convince me that on this vital issue the Imperial Parliament, as such, is unable or unwilling to do justice – I say that, if I am brought face to face with such a situation, the platform on which I have firmly stood crumbles away...

... my conduct has brought me into collision with political friends. It has, to a certain extent, divided the Unionist party in Ulster. It has made my own battle in South Tyrone harder perhaps than it need otherwise have been.

For the country, for the Union, for the people, there is no safety but in an honest effort to do justly between the two contending parties on this, the great Irish question..."

(Part Two to follow...)

0 comments:

Post a Comment