(Part One was posted recently, here)

Seán O'Faoláin founded The Bell in Dublin in 1940. Three years later he gave its pages over to comment about, and refutation of, a pamphlet which was published in August 1943 entitled Orange Terror: The Partition of Ireland. These articles appear in the handful of editions of The Bell that I picked up during the summer. Here's my attempt to summarise the story.

• Orange Terror: The Partition of Ireland

Its author was anonymously named 'Ultach' who later turned out to have been 33 year old James Joseph Campbell (1910-1979). His entry here in the Dictionary of Ulster Biography says that 'he subsequently modified his views'. He went on to have an influential career in the establishment in Northern Ireland's academia and broadcasting – but Orange Terror, hitting the streets during World War 2, spread like wildfire at the time and caused a furore. There had been much cross-community and cross-border co-operation during the war and especially the 1941 Blitz on Belfast, with strong messages of solidarity from O'Faoláin's former colleague Éamon De Valera, and Frank Aiken (see here).

The pages of a number of sequential editions of The Bell rang with various perspectives on Orange Terror. A correspondent called 'Ultach Eile' wrote in the November 1943 edition "It is no uncommon thing to find a minority who charge the State with unfair treatment; who charge that the working-class are subdivided into privileged and oppressed sections along a political line. What is uncommon is to find a government which instead of rebutting the charge just does not put a tooth on it".

So either the claims within Orange Terror were true, or the Northern Ireland Government of the day didn't have the ability, inclination or savvy to explain exactly how they were untrue.

• Banned

Orange Terror was banned by William Lowry KC, the Northern Ireland Minister of Home Affairs, under the Civil Authorities (Special Powers) Act in January 1944 'on the grounds that it is likely to be prejudicial to the preservation of peace and order in Northern Ireland'.

The debate about this in Stormont pointed southwards in attempted justification '... a recent decision of the Éire government in banning a certain Sunday paper...'. What we today call 'cancel culture' was rampant then – by February of that year something like 1600 books had already been banned by the Éire government including two of Seán O'Faoláin's early books – Midsummer Night Madness and Other Stories (1932) and Bird Alone (1936).

• 'We pride ourselves on the liberty our citizens enjoy'

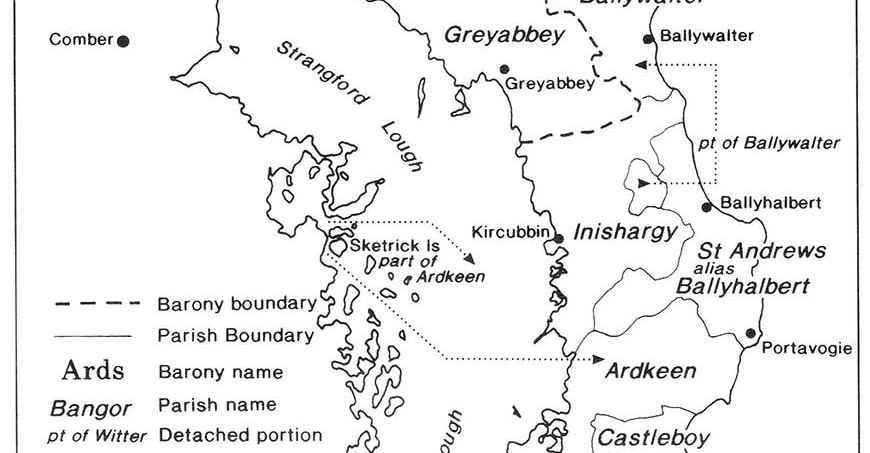

A prominent figure who strongly objected to the banning was the then Church of Ireland Dean of Belfast, the County Wicklow born William Shaw Kerr (1873–1960). During his career Kerr had held a number of Ulster curacies, starting at Shankill in Lurgan in 1897 and also ten years just up the coast from me at Ballywalter from 1901–1910 (pictured below).

Kerr was angered by the Stormont ban. He argued that Orange Terror '... was so grossly exaggerated that it defeated itself and it would have been better not to have banned it...' ; he wrote a stern letter to the Belfast News Letter on 20 January 1944 deploring 'state censorship of books'. Far from banning it, Kerr said that 'I believe its circulation should be encouraged'. Here's his letter, in which he quoted from John Milton's 1644 Areopagitica (full text online here) –

Kerr was already an established author, including of The Independence of the Celtic Church in Ireland in 1931, and Walker of Derry in 1938 (just in time to mark the 250th anniversary of the historic siege of the city of 1689). Kerr wrote a 12 page response to Orange Terror, entitled Ulster: A Rebuttal, which Sean O' Faoláin published in The Bell in February 1944.

• Reprinting the Rebuttal

The Ulster Unionist Council reprinted Ulster: A Rebuttal later that year as a pamphlet for wider circulation and re-titled it Slanders on Ulster: Reply to Orange Terror.

In May 1944 Douglas Savory, MP for Queen's University (and investigator of the wartime horror of the 1940 Katyn Massacre in Poland) supported Kerr's article and wrote an article for The Economist about the issues, where he made reference to even more examples of discrimination south of the border. These had been highlighted by Belfast-born Professor William Bedell Stanford of Trinity College Dublin in a publication earlier in 1944 entitled A Recognised Church: The Church of Ireland in Éire. St John Ervine would mine Kerr's rebuttal carefully for a chapter in his 1949 biography of the late Sir James Craig.

Publishing Slanders on Ulster did no harm to Dean W. S. Kerr's ecclesiastical career; he was consecrated Bishop of Down and Dromore at St Anne's Cathedral less than a year later in January 1945, a post he held for 10 years until his retirement in 1955.

..............

Fair play to both Dean William Shaw Kerr (who was also a Grand Chaplain of the Grand Orange Lodge of Ireland) and Seán O'Faoláin (former publicity director of the I.R.A.) for opposing the respective state censorships of their day, and for publishing and airing these issues.

This is a very complex period. I am way out of my depth on these issues. None of these issues are as simple as we are usually told.

But we know that people disagree. This is not a bad thing. From disagreement comes the hearing of a different perspective. From hearing comes learning. Understanding is enriched, and when new information is taken on board then opinions are changed. There is value in healthy disagreement.

Free speech is essential. The best antidote to bad speech isn't less speech, but more speech*.

..............

• A BBC article about Orange Terror and other banned literature is online here.

• Of course there's a Wikipedia page about it all.

* There is a very silly idea that 'old white men' are the only people who care about free speech. Well here is Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie saying pretty much the same thing, on BBC Newsnight earlier this week. Watch the specific part of her interview on BBC iPlayer here from 38:00, about cancel culture. She recently won the Women's Prize for Fiction (article here).