Culture is transmitted. People share things, adopt things, and (often unwittingly) absorb the community values that surround them. People change and adapt. New things come along, some old things endure, some are discarded. New people embrace those values and become part of the community. This is what makes life interesting, and Ulster is no different. In that regard culture is much more interesting to me than assumptions about ancestry.

It’s maybe easier to observe in America, where for example the wonderful musical duo the Loudermilk / Louvin Brothers, of Dutch or German ancestry, lived in the very Scotch-Irish world of northern Alabama and the southern Appalachians. Their ancestry wasn’t defining, but their cultural setting was.

I only knew three of my grandparents - my paternal grandfather, the local poet and three field homestead farmer William Thompson, died a long time before I was born. The other three were solidly culturally Ulster-Scots in every imaginable way, and so I am sure that he was too.

Yet it is highly presumptious to think that that’s all they were comprised of. A peek into their ancestry reveals some interesting potential twists. My maternal grandmother was Mary-Ann (Molly) Hamill (1918-1982). My paternal grandmother was Maggie-Anne (Madge) Coffey (1911-1995). These two surnames, Hamill and Coffey, are pretty much as old as it gets round here - older than the Lowland Scottish surnames which arrived here post-1606 with Hamilton & Montgomery.

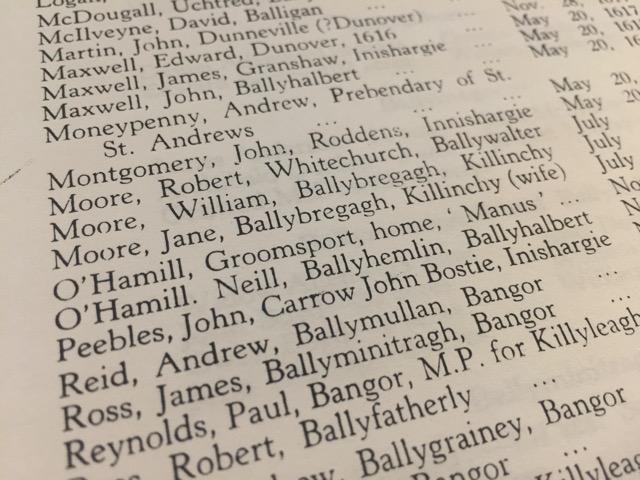

Both Coffey and Hamill can be found as surnames of the Irish tenants on James Hamilton’s east Down estates in the early 1600s. Neill and Manus O’Hamill lived at Ballyhalbert and Groomsport respectively, and Edward O’Coffie and his brother, whose first name is unrecorded, lived at Killyleagh. They weren't ‘driven out’ as the loaded stereotype would claim. These, and other Irish families, are referred to even in Sir James Hamilton’s will. It is entirely plausible that these are ancestors of my two grandmothers.

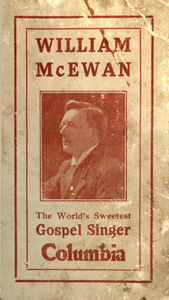

Their names are among those catalogued in Rev David Stewart’s landmark 1950s research The Scots in Ulster - that’s where the images on this post come from.

Ancestrally my grandmothers may well have had some pre-Plantation Irish elements, but culturally they were both Ulster-Scots. There’s a family tradition on the Hamill side, probably dating from the late 1800s or early 1900s, that a young Catholic girl from Donaghadee had fallen pregnant, was shunned by her family. A young Presbyterian man, a shopkeeper from Millisle, took pity on her, gave her a job and a room in his house, and eventually they got married. Surnames like Drennan and Carr/Kerr bubble around in that generation, I’m not precisely sure which apply to this - socially scandalous - couple.

Most of us, ancestrally, are a mixed bag. But culturally, my lot have been Ulster-Scots for as far back as anyone can recall. Prior to that, my white eyebrows and haplogroup I-M253 suggest a bit of Viking or Anglo-Norman in there.

Our actual lived experience, and the influence and values of our families and community, is what forms us culturally - not some imagined ancient past. We learn from our history but we live our culture, and our culture can take on new forms and be shared with others.

There’s a great letter from Rev Josias Welsh of Templepatrick in south Antrim who observed in 1632 that people recently arrived from England were quickly adopting Presbyterian culture. Shamrock, rose and thistle.

So when I was at a history talk event not that long ago, and not in my own locality - I was a bit shocked when the Q&A session at the end descended into a “they stole our land”. What is meant by “they”? And what is meant by “our”? I know fine well what was implied, but when your ancestry is probably on both sides of the argument then you can see how pointless it is.

And does one historical moment matter more than all other moments? Do the eras of conflict assume more importance than the eras of co-operation? Does the present generation inherit the culpability for the social problems of the past, but gain none of the credit for historical social co-operations? And how is that responsibility or credit tangibly measured?

In a way we are all either editors or audiences - editors in that we choose what we decide to cherish, audiences in that someone else’s editorial decisions are served up to us. These choices are made for good or for ill.

So where do you choose to draw the line?

2 comments:

It's interesting that you mention the presbyterian assimilation that occurred in Templepatrick; from as early as the 1640's, there appears in the records for the local presbyterian congregation such "Scottish" names as McGuckin and O'Donally. There was even a presbyterian minister from the village by the name of Jeremiah O'Quinn; more Gaelic Irish converted than is usually thought. Interestingly enough, O'Quinn actually ministered to Arthur Upton of the eponymous castle. There is also the example of John Clotworthy of Antrim castle; as staunch a presbyterian as Jenny Geddes, and who may have even took the convenant in Edinburgh during a visit in 1638. Neither man had any Scottish ancestry. Indeed, even that great presbyterian stalwart, Henry Cooke, was as much of English stock as he was Scots. Lastly there is the example of the huegenots, who due to the calvinist nature of their church, would have been far more amenable to presbyterianism than to the established church; the French roots of figures such as Henry Joy Mcracken, Robert Adrain and S.S.McClure are often obscured. A common habit exists of equating presbyterianism with Scottish descent, and indeed for good reason; however, this should not distract from the fact that presbyterianism developed more organically and from more divergent origins than is usually assumed.

Hello again Eamon. This is why culture is a more interesting dynamic to me that the 'strictures' of (assumed) ancestry or modern-day politics. Those are important but in a way fixed. Culture is a malleable thing, which has and can welcome the inclusion of others who choose to adopt its values and traits.

Faith in particular has that ability - to be persuaded or 'convicted' to adopt a set of belief regardless of one's own upbringing - is a pretty liberating, personal, experience. To be welcomed with open arms into a community to which one didn't previously belong is a wonderful thing.

Post a Comment